As part of Black History Month, I thought I would call attention to a writer I’ve “discovered” in the last two years. I’ve long been a fan of science-fiction literature, but had not read any for at least a decade or more except for the writings of Portland’s Ursula K. Le Guin. Then a close friend introduced me to Octavia E. Butler by giving me a bag full of her books. I devoured them within a few months, which led me to learn more about her. Butler wrote more than a dozen books and numerous short stories. To my surprise, I found out she passed away February 24, 2006 after a fall near her home in Seattle at the age of 58.

Butler’s personal story is inspiring. She grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood in Pasadena, California. Her father was a shoeshiner who died when Octavia was very young. Her single mom worked as a maid. Butler overcame poverty and dyslexia and worked as a dishwasher, telemarketer, and potato chip inspector before graduating from Pasadena City College and rising to the height of her field. She was the first African-American female novelist to excel in the male-dominated field of science fiction.

Octavia Butler/Photo by her friend Leslie Howle

Octavia’s work featured women of color as heroines and explored themes of race, eugenics, class, throwaway workers, dystopian economic divides, religion, global warming, and genetic manipulation. In 1995, because of her forward-thinking visionary writing, she received what is commonly known as a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Fellows Program, a prestigious award given by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Octavia was the first science-fiction writer to have won the award. She also won Nebula and Hugo awards, top science fiction honors. In 2010, she was inducted into to the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in Seattle.

I’ve read most of her books now, but it was Butler’s Parable of the Talents that especially spoke to me. I read it during the height of the Occupy Portland movement, and her descriptions of a dystopian future disabled by massive poverty, corporate takeovers, class wars, and anarchy resonated with me. The book’s protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, escaped violence-torn Los Angeles to travel northward for safety. She meets people along the journey and they form a new community. They are drawn to her stories presenting space travel as hope for the future and a chance to start anew. This idea thrilled me like it did when I was a child watching the 1969 moon landing or my favorite show at the time — “Star Trek” — which spoke of a utopian future.

In several of Butler’s novels, she describes the near-idyllic setting of the Pacific Northwest as a place people escaping the horrors of inner-city madness can live in peace and safety. That’s why in 1999, she moved to Seattle, the city she fell in love with on a book tour.

Butler’s novels and short stories feature African-American or African women as heroines. In Kindred, she writes of a black woman in 1976 who aimlessly works in dystopian jobs that go nowhere. She has no sense of history but hopes for a future with her husband who is white. She soon begins the first of six involuntary travels back in time to the antebellum South. She endures beatings and the horrors of slavery. Butler wrote Kindred in the 1970s because she felt young people of her generation were distant from the emotional impact of slavery as a legalized institution.

It’s amazing to me that Butler was the first widely read and studied African-American science-fiction novelist in America. There are countless YouTube videos of her interviews as well as young people of all colors and nationalities giving video reviews, readings, and even curious dramatizations of her novels. Butler’s multicultural novels pushed boundaries of race, gender, and humanity as she presented ideas ahead of her time that have become realities: inner city unrest, economic and class disparities, climate change disasters, and the power of the one percent.

Before her death, Octavia was quoted as saying she wanted to write a follow-up to the Parable novels with one that would reflect her move to Seattle in which her characters achieve their dream of reaching Alpha Centauri to save humanity. I can understand how she felt. The problems of the world seem too overwhelming, and there’s a strong part of me that believes we should start all over somewhere else. But the reality is that this is our world. Octavia’s prophetic writing has come true in many cases. Let’s hope her vision of humanity surviving despite the struggles remains true.

Octavia E. Butler’s hope involved working with young writers of color and encouraging a new generation of writers at the prestigious Clarion and Clarion West writers’ workshops. After her death, friends and colleagues of the Carl Brandon Society, a group dedicated to raising awareness of race and ethnicity in speculative literature, started the Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship to fund scholarships for writers of color to study at Clarion. This year the group published an e-book called Bloodchildren: Stories by the Octavia E. Butler Scholars (the title pays homage to her short story “Bloodchild”). The book is an anthology by student writers of color and proceeds benefit the memorial scholarship fund. To learn more, visit:www.carlbrandon.org/bloodchildren.html.

Remembering Octavia Butler

As part of Black History Month, I thought I would call attention to a writer I’ve “discovered” in the last two years. I’ve long been a fan of science-fiction literature, but had not read any for at least a decade or more except for the writings of Portland’s Ursula K. Le Guin. Then a close friend introduced me to Octavia E. Butler by giving me a bag full of her books. I devoured them within a few months, which led me to learn more about her. Butler wrote more than a dozen books and numerous short stories. To my surprise, I found out she passed away February 24, 2006 after a fall near her home in Seattle at the age of 58.

Butler’s personal story is inspiring. She grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood in Pasadena, California. Her father was a shoeshiner who died when Octavia was very young. Her single mom worked as a maid. Butler overcame poverty and dyslexia and worked as a dishwasher, telemarketer, and potato chip inspector before graduating from Pasadena City College and rising to the height of her field. She was the first African-American female novelist to excel in the male-dominated field of science fiction.

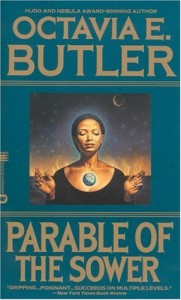

Octavia’s work featured women of color as heroines and explored themes of race, eugenics, class, throwaway workers, dystopian economic divides, religion, global warming, and genetic manipulation. In 1995, because of her forward-thinking visionary writing, she received what is commonly known as a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Fellows Program, a prestigious award given by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Octavia was the first science-fiction writer to have won the award. She also won Nebula and Hugo awards, top science fiction honors. In 2010, she was inducted into to the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in Seattle.

I’ve read most of her books now, but it was Butler’s Parable of the Talents that especially spoke to me. I read it during the height of the Occupy Portland movement, and her descriptions of a dystopian future disabled by massive poverty, corporate takeovers, class wars, and anarchy resonated with me. The book’s protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, escaped violence-torn Los Angeles to travel northward for safety. She meets people along the journey and they form a new community. They are drawn to her stories presenting space travel as hope for the future and a chance to start anew. This idea thrilled me like it did when I was a child watching the 1969 moon landing or my favorite show at the time — “Star Trek” — which spoke of a utopian future.

In several of Butler’s novels, she describes the near-idyllic setting of the Pacific Northwest as a place people escaping the horrors of inner-city madness can live in peace and safety. That’s why in 1999, she moved to Seattle, the city she fell in love with on a book tour.

Butler’s novels and short stories feature African-American or African women as heroines. In Kindred, she writes of a black woman in 1976 who aimlessly works in dystopian jobs that go nowhere. She has no sense of history but hopes for a future with her husband who is white. She soon begins the first of six involuntary travels back in time to the antebellum South. She endures beatings and the horrors of slavery. Butler wrote Kindred in the 1970s because she felt young people of her generation were distant from the emotional impact of slavery as a legalized institution.

It’s amazing to me that Butler was the first widely read and studied African-American science-fiction novelist in America. There are countless YouTube videos of her interviews as well as young people of all colors and nationalities giving video reviews, readings, and even curious dramatizations of her novels. Butler’s multicultural novels pushed boundaries of race, gender, and humanity as she presented ideas ahead of her time that have become realities: inner city unrest, economic and class disparities, climate change disasters, and the power of the one percent.

Before her death, Octavia was quoted as saying she wanted to write a follow-up to the Parable novels with one that would reflect her move to Seattle in which her characters achieve their dream of reaching Alpha Centauri to save humanity. I can understand how she felt. The problems of the world seem too overwhelming, and there’s a strong part of me that believes we should start all over somewhere else. But the reality is that this is our world. Octavia’s prophetic writing has come true in many cases. Let’s hope her vision of humanity surviving despite the struggles remains true.

Octavia E. Butler’s hope involved working with young writers of color and encouraging a new generation of writers at the prestigious Clarion and Clarion West writers’ workshops. After her death, friends and colleagues of the Carl Brandon Society, a group dedicated to raising awareness of race and ethnicity in speculative literature, started the Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship to fund scholarships for writers of color to study at Clarion. This year the group published an e-book called Bloodchildren: Stories by the Octavia E. Butler Scholars (the title pays homage to her short story “Bloodchild”). The book is an anthology by student writers of color and proceeds benefit the memorial scholarship fund. To learn more, visit:www.carlbrandon.org/bloodchildren.html.

Read The Asian Reporter in its entirety! Go to:Â www.asianreporter.com/completepaper.htm

About the author

EditorDmae Roberts, host/producer of Stage & Studio